1. Introduction

The Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) set aside is getting a fair share after they’ve been left out for so long. These schools have been lifelines for African American communities, helping people get an education despite facing a lot of unfairness. The recent Executive Order is like a big promise to make things right. It shows that the government is serious about giving Black Americans a fair shot at good education and jobs. It sets up special groups and rules to make sure HBCUs get the support they need to thrive. It’s like saying, “Hey, these schools matter, and we’re going to do everything we can to help them succeed.” It’s a step forward in making things fairer for everyone.

2. History and background

Richard Humphreys founded the African Institute (now Cheyney University) in Pennsylvania in 1837, establishing it as the oldest Historically Black College and University (HBCU) in the United States, with a mission to provide free African Americans with practical skills for employment. The curriculum included basic subjects like reading, writing, and math, along with religious and industrial arts education. In the 1850s, three more HBCUs were established: Miner Normal School (1851) in Washington, D.C.; Lincoln University (1854) in Pennsylvania; and Wilberforce (1856) in Ohio, the latter being the first HBCU operated by African Americans. The provision of education for African Americans in early America was met with diverse opinions, with some deeming it unnecessary and even criminal, while others recognized its essential nature.

While the majority of HBCUs (approximately 89%) are situated in the southern United States, they also exist in Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and West Virginia. Notably, North Carolina hosts eleven HBCUs, Louisiana seven, and Alabama twelve. Despite being perceived as a homogeneous group, HBCUs exhibit diversity across various dimensions, including academic distinction, socioeconomic status, and student demographics. They encompass diverse classifications, ranging from public to private, denominational, liberal arts, land-grant, and independent university systems, serving both single-gender and coeducational populations. These institutions vary in size, with enrollments ranging from fewer than 300 to over 11,000 students.

3. Contributions and Success stories.

From the late 1800s to the late 1900s, HBCUs thrived despite laws and policies that barred Black Americans from attending most colleges and universities.

Notable achievements during this period:

HBCUs provided undergraduate training for 75% of all Black Americans holding a doctorate degree.

75% of all Black officers in the armed forces were HBCU graduates.

80% of all Black federal judges also hailed from HBCUs.

The General Services Administration (GSA) actively supports the goals of the White House Initiative for HBCUs.

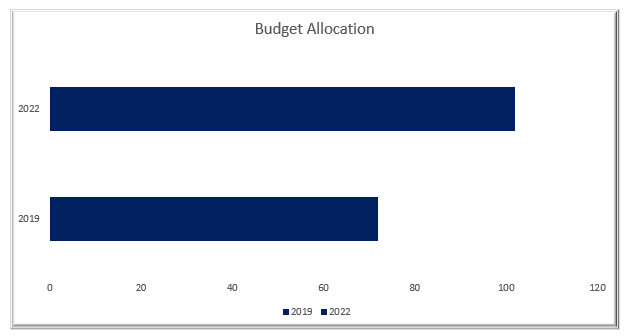

Approximately 85% of HBCUs are located within a qualified HUBZone. In fiscal year 2022, DOD allocated $102 million in research funding to HBCUs, up from $72.5 million in fiscal year 2019.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) aims to increase annual contracting with HBCUs to $3 million.

Black students earned 44 percent of the 5,300 associate degrees, 81 percent of the 32,800 bachelor’s degrees, 70 percent of the 7,600 master’s degrees, and 61 percent of the 3,000 doctor’s degrees conferred by HBCUs in 2021–22.

4. Executive Order

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) grappled with systemic barriers, impeding access to resources compared to other higher education institutions. Despite educating a higher percentage of lower-income, Pell-grant-eligible students, financial disparities persisted, with HBCUs receiving less tuition revenue and possessing smaller endowments. The challenges intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic, exposing issues in physical and digital infrastructure, and underscoring the urgent need for equitable funding. The post-Executive Order landscape introduces transformative measures, including the White House Initiative providing advice to the President, the Interagency Working Group fostering collaboration among government agencies, and the President’s Board of Advisors offering diverse perspectives aligned with the PARTNERS Act. Annual Agency Plans ensure transparency and accountability, outlining efforts to bolster HBCUs’ capacity. The National HBCU Week Conference facilitates collaboration, while Progress Monitoring, led by the Executive Director, ensures annual reporting on the Initiative’s advancements, solidifying transparency, and accountability in achieving educational equity, excellence, and economic opportunity for HBCUs.] ep

5. Why HBCUs are not still succeeding?

The recent executive order allocating resources to Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) represents a significant and commendable step towards addressing historical inequities. This initiative demonstrates the government’s commitment to fostering a more equitable and inclusive higher education landscape.

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that this is just the beginning. To truly ensure the long-term success and flourishing of HBCUs, we must sustain and build upon this momentum. Instead of relying on government handouts, HBCUs should explore alternative solutions. This includes:

-

Diversifying funding sources: HBCUs should seek private donations, invest in revenue-generating ventures, and explore partnerships with the private sector.

-

Building community partnerships: Collaboration with local businesses, organizations, and individuals can provide resources and support beyond government involvement.

-

Focusing on innovation and entrepreneurship: Encouraging and fostering student and faculty entrepreneurship can create sustainable income streams and empower individuals to take control of their own success.

-

Leveraging technology: Utilizing online learning platforms and other technological advancements can improve educational access and efficiency without relying on government funding.

Moving forward, addressing the following areas remains critical:

-

Continued investment: While the set-aside is a positive step, consistent and adequate funding is crucial to ensure long-term sustainability and address ongoing challenges.

-

Targeted initiatives: Addressing historical resource disparities and tackling specific needs like infrastructure development, student support programs, and access to research opportunities requires focused efforts.

-

Collaboration and partnerships: Fostering collaboration between HBCUs, policymakers, and the private sector can leverage expertise, resources, and innovative solutions.

By working together to overcome existing obstacles and building upon the government’s commendable initiative, we can ensure that HBCUs not only survive but thrive, achieving their full potential in nurturing future generations of leaders and scholars.

Furthermore, we believe engaging with HBCUs should be driven by genuine interest and mutual benefit, not government mandates. Collaborations should be organic and based on shared values and goals, fostering genuine partnerships that benefit both parties without government interference.